FREE SHIPPING: EU 60€. FOR U.S. PURCHASES, HERE

And we return to the women writers and their wonderful way of looking at the world. And to create it. When I read “Pilgrim at Tinker Creek” something caught me from the first of its pages. The image of that awakening in which the author discovers her body covered with small bloody tattoos, like small roses, produced by the paws of an old cat that had gone out to hunt at night, is disturbing to say the least. Looking at nature through her eyes is a gift. A nature of which, as she says, you cannot separate its beauty from its cruelty and violence. Her apparent idealism has a hard and analytical reverse, which is of a humanity that disarms and predisposes.

“Pilgrim at Tinker Creek” is full of beautiful images of a shocking lyricism, close to that of Emily Dickinson, but much more direct and sharp. Also of deep explorations in nature and in the soul, tinging some stories with an almost pantheistic religious feeling that is always disturbing, because despite its forcefulness it does not want to convince anyone, because it always involves a search. And it is that the curiosity of this woman born in Pittsburgh in 1945, has been and is inexhaustible, and as she says, a great source of happiness.

If Rachel Carson had known her, she would surely have seen in her that “sense of wonder” that she called so much. Without a doubt, Annie, and her ability to be amazed is something that rubs off on you, as you read her.

Also, she is a poet, and it shows. The light that inhabits her writings is very particular. The texture of her sentences gives her ideas and reflections a dimension that goes beyond prose and essay. Not because she talks about great things (which he actually does). She can both advise you on how to make a snowman and give you a recipe for cooking a muskrat, but always with her ability to find treasures in the most unexpected places. Also familiar places. Because the her stories are close. There are no great explorations, nor especially remote and wild landscapes in Tinker Creek (where she lived for a while). For her, the nature and the mystery of it, is found everywhere

In “Teaching a Stone to Talk” (great title, which already puts us on notice), another of his non-fiction prose books, Dillard can make you cry with the description of a tree, a micro mammal or an island, and then explain with scientific forcefulness (but without a hint of superiority) the complex framework and the secrets of an ecosystem as complex as that of the Galapagos Islands. She can. She knows how to enjoy and be inspired both by a finch that pecks at her hair and by the scientific reports that warn us of climate change. Nothing escapes her capacity for wonder. And the best. She knows how to transmit and share it with an impeccable rhythm. Love for nature in its purest form and great literature.

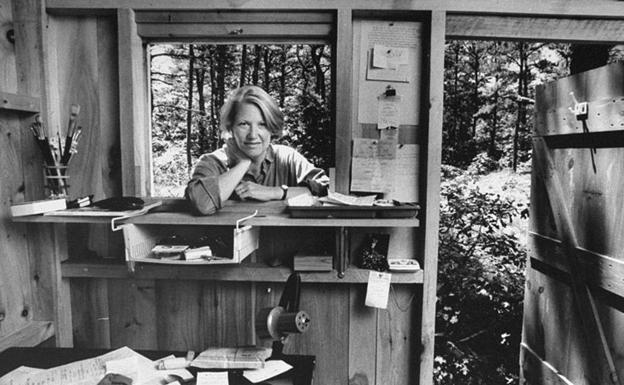

Drillard, became interested in different religions such as Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, even Inuit spirituality. He converted to Roman Catholicism for a time, but abandoned Christianity because of the absurdity of some of its doctrines. That spiritual quest fascinates me in her. If I had her in front of me one day, I would ask her about that drift. It makes me very curious that being so close to nature and its understanding, at an unusual level of depth, she won’t find answers in it (because she did find questions). That she did not find in the presence of a tree, or in the silence of the stars, enough comfort. Possibly I’m getting the question wrong, and it was precisely these things that made her look further. I also don’t know if I would be able to ask her. If I would dare. Perhaps, I just remained silent, looking into those eyes of hers and trying to infect me, even if only a little, with the disarming way of looking she has.